Henrik Fisker stands with the Fisker Ocean electric vehicle after its unveiling on the Manhattan Beach Pier ahead of the Los Angeles Auto Show and AutoMobilityLA in Manhattan Beach, California. on November 16, 2021.

Patrick T Fallon | AFP | Getty Images

Fisker on Monday became the latest all-electric vehicle startup to file for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection amid weak consumer demand, significant cash burn and operational and product problems.

The writing has been on the wall for investors for some time, as Fisker expressed concerns about its ability to continue as a company in February, leading to its charismatic founder and CEO Henrik Fisker disappearing from social media and the spotlight.

It is the latest in a series of electric vehicle company collapses. Other companies backed by special purpose acquisition companies (SPAC) have also filed for bankruptcy protection. This list includes companies such as Proterra, Lordstown Motors and Electric Last Mile Solutions. Others such as Nicholas And Faraday future remain in business but are trading for less than $1 per share amid operational challenges, missed targets and general industry headwinds.

It’s also a bit of déjà vu, as this is Henrik Fisker’s second car company, both operating under his last name, to file for bankruptcy.

The new filing comes after Fisker failed to secure investment from a major automaker to stay afloat. Nearly four years ago, Fisker announced plans to go public through a reverse merger with an Apollo-backed SPAC that valued the company at $2.9 billion. The deal netted Fisker more than $1 billion in cash.

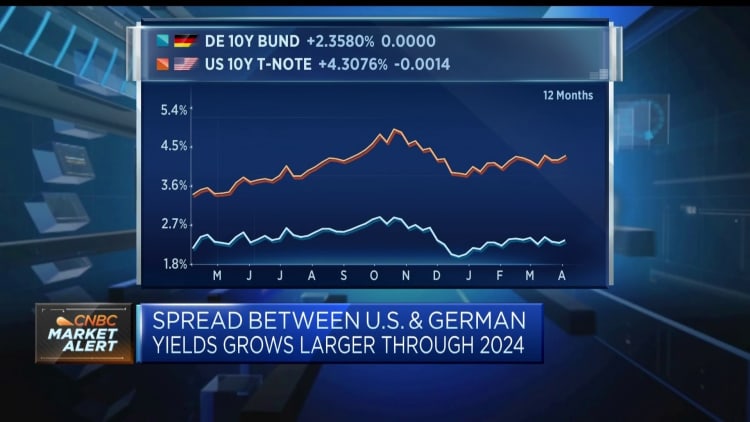

Fisker, like many other companies at the time, was buoyed by low interest rates and a bullish move on Wall Street toward electric vehicles following the rise of the U.S. electric vehicle leader Tesla.

“You looked at the success of Tesla, and Tesla was more of an anomaly than an example,” said Sam Abuelsamid, senior research analyst at Guidehouse Insights.

But consumer acceptance of electric vehicles has grown more slowly than expected, costs have risen and investor interest in EVs other than Tesla has dried up. The company also faced significant problems in its operations as well as the launch of its first product, the Ocean SUV EV.

Focus on software

When it went public via a SPAC in 2020, Henrik Fisker compared the company to US electric vehicle leader Tesla. He also pointed to the production relationships with the Canadian automotive supplier Magnacompares it to the relationship between Apple and Foxconn.

Unlike most of its competitors, the automaker hired a third-party manufacturer to build the Fisker Ocean crossover. The partnership with Magna was intended to be an “asset-light” strategy, as Fisker described it, allowing the company to save money and focus on differentiating technologies such as software.

Abuelsamid said such a strategy was not inherently bad, but called the company’s management incompetent and pointed the finger at Geeta Gupta-Fisker, the company’s chief financial officer and chief operating officer. Gupta-Fisker is also the wife of Henrik Fisker.

“This approach can be implemented,” he said. “The problem in the Fisker case that I underestimated was … management incompetence.”

The company wasted cash and recalled thousands of Ocean SUVs in North America and Europe last month due to problems with the vehicle’s software.

According to the Chapter 11 filing, the company owes debt to software and engineering companies such as: B. Amounts in the millions Adobe, SAP America, Manpower group and Prelude Systems, among others. CNBC parent company NBCUniversal is also listed as a top creditor.

“[The auto industry is] capital intensive. You’re trying to balance production and consumer demand, and if they have any problems with the vehicle, money needs to be allocated for that,” said Stephanie Valdez Streaty, Cox Automotive Director of Industry Insights. “Even if this is not the case.” have other income like [internal combustion engines] financing it…that makes it a big challenge.”

Its operating unit, Fisker Group Inc., estimated assets at $500 million to $1 billion and liabilities at $100 million to $500 million.

At the end of last year, Fisker had $530 million in inventory as the company sold just 4,700 of the more than 10,000 Ocean electric vehicles produced in 2023.

Seen

For Henrik Fisker, a renowned automotive designer who designed the BMW Z8 and Aston Martin DB9, it’s déjà vu.

His first eponymous company – Fisker Automotive – filed for bankruptcy protection in 2013, shortly after he left the company. The company later sold its assets to China’s Wanxiang Group for $150 million.

The second time was supposed to be better for the founder, who said he learned from past mistakes with his former bankrupt company.

“Because I’ve done this before, I’m in a unique position to kind of leverage the lessons learned, which is very rare, especially in the automotive industry,” he said in 2017, a year after founding the new company.

But the parallels between the two failed companies are hard to miss.

Both companies were heavily hyped, largely because Fisker itself claimed they would revolutionize the industry. They were fueled by “free” money – first federal funds, more recently Wall Street – on the premise that “green” or electrified vehicles were the future of the auto industry.

Additionally, both faced significant quality issues that led to recalls. The first Karmas manufactured by Fisker were recalled in 2011 due to battery safety issues and fire hazards.

Both companies also changed direction and priorities several times.

After less than half of the more than 10,000 vehicles produced were delivered through a direct-to-consumer approach similar to Tesla’s model, Fisker turned to a dealer-based sales model in January.

This time, however, there was a crucial difference. With the failure of the second Fisker, its investors, not American taxpayers, were left in the lurch. While Henrik Fisker’s first company was bolstered by a $529 million federal loan – $139 million of which the government lost – the second company was funded by Wall Street’s optimism about SPACs and electric vehicles. The stock was delisted in April.

A Fisker spokesman said in a statement early Tuesday that the company was “proud of our accomplishments” but decided Chapter 11 was the best option.

“Like other companies in the electric vehicle industry, we have faced various market and macroeconomic headwinds that have impacted our ability to operate efficiently,” the spokesperson said in a press release. “After evaluating all options for our company, we concluded that selling our assets under Chapter 11 is the most viable path for the company.”

Don’t miss these exclusives from CNBC PRO

Source link

2024-06-18 18:29:37

www.cnbc.com