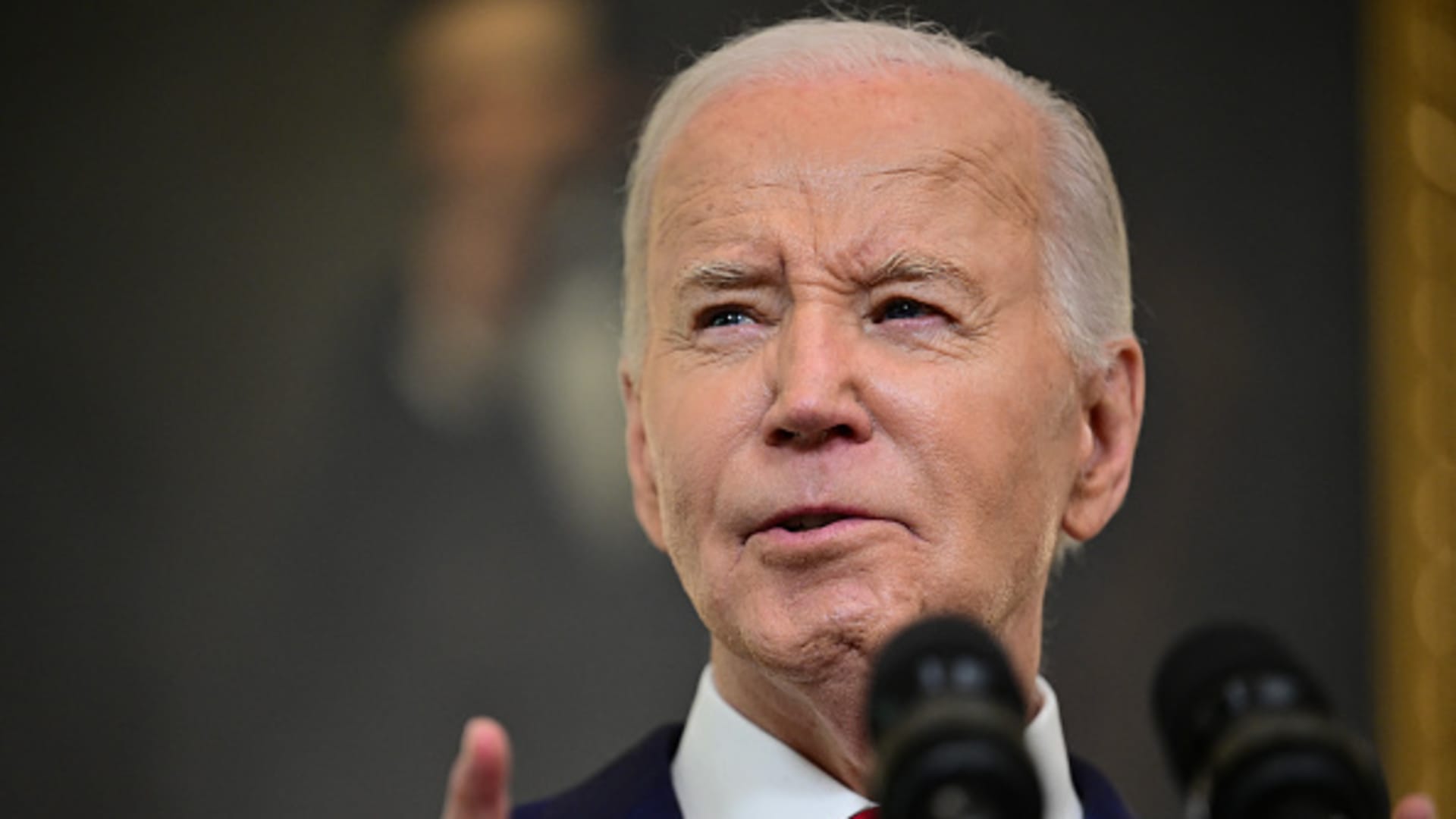

President Biden’s announcement on Wednesday of giving Intel an $8.5 billion federal grant to build some of the world’s most advanced computer chips is one of the most remarkable American experiments in industrial policy since Dwight D. Eisenhower’s federal funding used to build the country’s highway system.

But rather than a fresh start in America’s efforts to restore a technological capability it invented and then all but lost, there is significant risk that this could be the culmination of the effort.

When the CHIPS and Science Law was passed two years ago, it was promoted as a down payment on the kind of long-term investments in critical economic sectors that made Taiwan the world’s leading player in chip manufacturing. It’s a strategy China began pursuing nearly a decade ago, pouring new money year after year into chips and high-performance batteries, quantum computing and artificial intelligence, to name a few.

But while Mr Biden celebrated the construction of the Intel plant as a turning point in US industrial and national security strategy, there is no prospect of a follow-up program any time soon. And quietly, Congress has cut the billions of dollars that were appropriated but never fully allocated for research, training and manufacturing.

As Mr. Biden assesses the immediate benefits of the Intel investment — 10,000 manufacturing jobs in Arizona, New Mexico, Oregon and Ohio, and 20,000 construction jobs to get things rolling — many in his administration privately fear that their strategy This may not survive the moment of political polarization.

That’s why Mr. Biden and his Commerce Secretary, Gina Raimondo, aren’t talking much about the level of additional government investment that may be needed if the country is serious about boosting investment in everything from the most expensive semiconductor factories to the auto industry’s technology makers, which need emissions regulations fulfill.

“President Biden often spoke of this law as a ‘watershed moment,’ a new role for federal investment in the toughest problems in high technology,” said Doug Calidas, a fellow at Harvard’s Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs and a senior vice president of Americans for Responsible Innovation, an advocacy group for new technologies, especially artificial intelligence.

There was a hint of that concern in Intel CEO Patrick Gelsinger’s comments to reporters Tuesday night.

“It can’t be fixed in a three- to five-year program,” Mr. Gelsinger said. “I think we need at least a CHIPS 2 to do this job.”

That was an optimistic assessment. Many involved in the industry say they believe federal investments will need to be repeated as technological challenges change, while also assessing which technologies are simply too critical for the United States to depend on foreign supply chains. Previous attempts to bolster the chip industry with one- or two-stage investments, when Japan was the main competitor, failed spectacularly.

The passage of the CHIPS Act in 2022 was the result of a confluence of extraordinary events. Most vividly, the discovery during the coronavirus pandemic was how fragile the supply of critical goods can be – from surgical masks to vaccine precursors to common chips needed to make cars and washing machines. Added to this was the growing fear of China’s power, which could both disrupt the American economy and threaten Taiwan, where more than 90 percent of the world’s most complex and advanced semiconductors are manufactured.

Ms. Raimondo and Avril D. Haines, the director of national intelligence, briefed senators in the weeks before the bill’s passage about the notable vulnerabilities of America’s defense industry and how shutting down certain technologies could allow it to fire missiles and increase production of fighter jets Stop. The specter of a rising, manipulative China holding Taiwan’s semiconductor manufacturing centers hostage brought enough Republicans to win a truly bipartisan majority. The bill passed in the Senate with a vote of 64 to 33.

Even then there were doubters. Morris Chang, the MIT-educated engineer who left Texas Instruments and founded the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company, argued that money alone would not be enough to reproduce the magic he created. He described the billion-dollar subsidies as “a very expensive and futile exercise.”

At the heart of Mr. Chang’s criticism was the argument that American engineers would not put in the grueling hours and perfectionism required even if Intel copied Taiwan Semiconductor’s core strategy and became a “foundry” designed by companies like Apple and Nvidia Chip manufacture will be successful.

But there was another criticism coming from industrial policy advocates: that Mr. Biden’s push to bring manufacturing home came too late and that the bill was far too small to spur the private investment that are necessary for a real renaissance of production.

The politics of an election year bring yet another layer of difficulty.

Former President Donald J. Trump has regularly launched attacks on another form of industrial policy: Mr. Biden’s incentives to buy electric vehicles, a key part of his climate agenda.

These cars have become part of Mr. Trump’s diatribes on the campaign trail. He argued without evidence that electric cars would “kill” the American auto industry and said the Biden administration had “ordered a direct hit on manufacturing in Michigan” by luring buyers to electric vehicles through tax breaks and other subsidies.

But even Mr. Biden seems somewhat hesitant to fully support his own policies. The original CHIPS Act authorized the United States to spend $35 billion through government agencies on science and innovation research in 2025; Mr Biden’s budget request, released last week, is closer to $20 billion.

“The rhetoric is much more impressive than the budget numbers,” Mr. Calidas said.

Source link

2024-03-20 22:27:36

www.nytimes.com